Saturday, May 1, 2010

Karachi to Melbourne Tram!!

Tram decorated in Melbourne - Truck Art style. Crowd is loving it!!

Source: http://video.google.ca/videoplay?docid=1892581750172057106&q=w11+tram#

Thursday, April 29, 2010

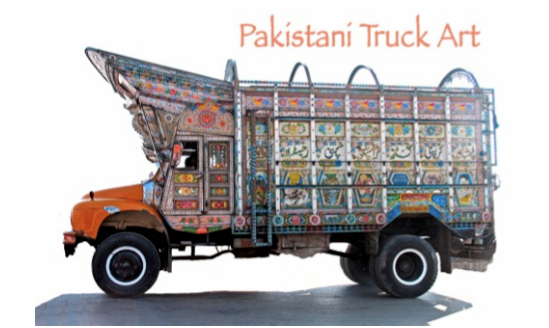

Moghul Paintings & Pakistani Truck Art

A strong link can be made with the 'Truck Art' style of painting and 'Moghul Art'. Truck Art stems Moghul Art, the same sort of style is applied, the same sort of ornamentation is applied and similar colour is used. More so, I signified there are the same themes present in Moghul Paintings as well as Truck Art.Themes such as:

1) Political Messages (Relative to battles in Moghul Art)

2) Folktales/Poetry (Most miniature paintings are based on folktales)

4) Objects & Decorations (Not valid for Moghul paintings per say, however there is a lot of decorations within the paintings - as far as Truck Art is concerned we are addressing these objects as being 3-D, hence it is not appropriate for Moghul Art)

5) Personal Messages (Once Again not valid for Moghul Paintings)

The intricate detailing and filling of all space is very similar between Truck Art and Moghul Paintings. Moghul Paintings consisted of a lot of images of birds (peacocks), lions, flowers, scenic views, etc. And this is all still present in modern day Pakistani Truck Art.

Source: http://teachartwiki.wikispaces.com/Mughal+and+Rajput+Painting+16th-18th+Century?f=print

Source: http://www.exoticindiaart.com/article/mughal/

Tuesday, April 13, 2010

Truck Art Studies

Source: http://www.newsline.com.pk/NewsJul2009/heritagejuly.htm

As someone who collects and studies inscriptions on Pakistani trucks, I decided to write about these inscriptions, not only to understand the world view of the drivers and painters who write them, but also explore whether they provide evidence that the common man has not succumbed to the militant version of Islam that deems such art outside the bounds of a moral society. Could these inscriptions on trucks give us a peep into our culture, on which we could hope to build a tolerant Pakistan when this terrible, nerve-wrecking war is over? There did not seem much promise in this line of inquiry, but the truck inscriptions proved so mesmerising that I could not but proceed with my research in Rawalpindi, Peshawar, Quetta, Hyderabad and Rahim Yar Khan.

The study of truck art is not a field that has gone completely unexplored. Professor Mark Kenoyer, a famous archaeologist who has been conducting field research in Pakistan for close to two decades, told me in the autumn of 2008 how he had taken a decorated truck from Karachi to the United States.

“The funny thing is that it landed in LA and then we had to drive it across four time zones to DC for the 2002 Smithsonian Folk-life Festival.”

I was collecting inscriptions on Pakistani trucks at that time and I found that a number of people had collected truck art and even inscriptions. Jamal J. Elias, a Pakistani scholar now in an American university, is probably the foremost scholar in the field and he is writing a book on the subject. German scholars, too, had shown interest in the subject, and I saw a book by Anna Schmad in German called Die Fliegenden Pferde vom Indus (The Flying Horses of Indus) complete with pictures and details. Even Pakistanis, normally indifferent to the richness and diversity of their own country, have taken interest in these inscriptions. Sarmad Sehbai has made a film about the decorated trucks. More to the point for my work, there are two collections of truck inscriptions published by the Parco Pak-Arab Refinery, entitled Pappu Yar Tang na Kar (Do not bother me, friend Pappu) – a common humorous saying on many trucks. Part 1 consists of Urdu couplets, some with a risqué bent, along with aphorisms. Part 2 consists of the Urdu poet Ghalib’s couplets on rickshaws, taxis and trucks.

For my own study, I chose around 627 trucks registered in the NWFP, the Punjab, Sindh and Gilgit/AJK, and the inscriptions on them were noted and photographed. The inscriptions were then divided into the following themes:

Advisory: Of an advisory nature and about life in general. For example, Phal mausam da gal vele di (The best fruit is that of the season and the best saying is that which is appropriate for the occasion).

Driver’s life: Pertaining to the driver’s life of perpetual travel, of not having a fixed home and of taking pride in his profession, for instance Driver ki zindagi maut ka khel hai/Bach gaya to central jail hai (The driver’s life is a game of death/Even if he survives there is the central jail).

Fatalism: Pertaining to the idea of there being a fixed, unalterable destiny; predestination; qismat with all its variant forms, e.g. Nasib apna apna (To each his own destiny).

Goodness: General goodwill and good wishes for all, e.g. Khair ho aap ki (I wish you a blessed life).

Islam: Sayings from the Quran, references to Islamic mystics (Sufis), pictures of sacred places in Islamic culture and religious formulas e.g. Bismillah (In the name of Allah).

Islamic fundamentalism: A sub-theme of the above, these refer to tabligh (proselytising), the Taliban (Rashid, 2000) and exhortations to say one’s prayers. These were uncommon some years back and, in view of the increasing militancy misusing the name of Islam in Pakistan, these inscriptions were tabulated separately e.g. Dawat-e-tabligh zindabad (Long live the invitation to proselytise).

Islamic mysticism: Also a sub-theme of the Islamic inscriptions. These refer to some reputed Sufi shrine or idea, e.g. Malangi sakhi Shahbaz Qalandar di (I am a female devotee of the generous Shahbaz Qalandar).

Devotion to Mothers: Pertaining to love and respect for one’s mother, e.g. Man di dua jannat di hawa (A mother’s blessings are like the breeze of paradise). Nationalism: Pertaining to Pakistani nationalism, e.g. Pakistan zindabad (Long live Pakistan).

Patriotism: Pertaining to love for one’s native area e.g. Khushab mera shaher hai (Khushab is my city).

Romance: Pertaining to romantic love, flirtation, desire, aesthetic appreciation of (almost always female) beauty and, sometimes, the mildly erotic, e.g. Rat bhar ma’shuq ko paehlu men bitha kar/Jo kuch nahin karte kamal karte haen (Those who spend the whole night with the beloved next to them/And still do nothing, verily perform a miracle!)

Trucks: Pertaining to the truck itself. The truck is often portrayed as being feminine. Trucks are given feminine names in other countries, including the US, but in Pakistan, Muslim female names are not used for trucks. Common titles such as princess (shahzadi) are used, e.g. Japan ki shahzadi [Urdu] (Japan’s princess).

Explicitly religious symbols, images and inscriptions in Arabic are often found on the front and top of the truck. Sometimes, inscriptions also appear either on the bumper or on the engine itself. They also appear on the back and even on the sides.

However, it is on the front of the truck that the name of the sacred is found, Arabic being a sacred language for Muslims.

These inscriptions are, however, commonplace among Pakistani Muslims in daily life. They are considered auspicious and are spontaneous cultural habits. They do not indicate any special religious commitment, unlike the inscriptions gathered under the theme of ‘Islamic fundamentalism.’

The ‘fundamentalist’ type of Islam denies intercession by saints and rejects mystic (Sufi) practices and folk Islam. It takes several forms such as Wahhabbism (or Ahl-i-Hadith in South Asia) and the Deobandi sub-sect, as well as the more fundamentalist and militant interpretations of the last few decades. Some trucks, for instance, carry exhortation to prayers: ‘Namaz rah-e-nijat hai’ (Prayer is the path to salvation). Jamal Elias says he noticed this development for the first time in 2003, after four years of fieldwork on Pakistani truck decoration. He goes on to link it to the inspiration of the Tableeghi Jama’at of Maulana Ilyas (1885-1944).

Such inscriptions, however, rarely appear on the top of trucks. In Pakistan, the Taliban are the most noted fundamentalists and, therefore, the inscriptions linked to fundamentalists are generally about the Taliban (Taliban zindabad or Long live the Taliban is one of the inscriptions on numerous trucks) or prayers, fasting and proselytising in order to establish the Shariah. These have appeared only in the last few years and are found more on the trucks of the NWFP than in other regions.

The mystical inscriptions are those which are specifically about Sufi saints or shrines. This sub-genre is part of the Pakistan zeitgeist. Popular poetry and songs are frowned upon by the fundamentalists, who regard it as a form of seeking intercession in wordly matters from someone other than God (shirk).

The back of the truck is for inscriptions which are meant to be read as the truck passes by other vehicles. Here one finds mostly romantic inscriptions.

Most inscriptions draw on the conventions of the ghazal, the themes of which are unrequited romantic love, appreciation of female beauty, the fickleness of life and fatalism. While there is much eroticism in the Lucknow school of poetry, it is the more idealised, ethereal and emotional style of the ghazal which prevails. While some of the couplets of the classical masters of the ghazal, such as Ghalib or Mir Taqi Mir are in circulation on trucks, most drivers choose verses from unknown poets or sometimes from modern, popular ones such as Ahmed Faraz. The most frequently occurring inscriptions on romantic themes are as follows:

Ae sher parhne wale zara chehre se zulfen hata ke parhna/Gharib ne ro kar likha hai zara muskura ke parhna (O reader, read this couplet after removing the tresses of hair from your face/A poor man has written this, so please smile while reading it) and: Anmol daam dunga ik bar muskura do (I will give you incomputable wealth if only you smile but once).

Another one of the most ubiquitous ones is: Dekh magar piyar se (Look at me, but with love).

The examples given above are not drawn from Urdu’s large body of amorous poetry, but have been written by unknown poets who do not appear to know the strict rules of versification in Urdu. However, the stance found in the ghazal – the poet supplicating to an indifferent and fickle beauty for favours – is omnipresent.

Fatalism is very much a part of Pakistani folk belief. In Islamic philosophy, it is called masala-e-jabr-o-qadr (loosely translated as predestination and free will) and, at least in its more extreme forms, completely denies free will. Among ordinary people, however, the denial of free will goes hand-in-hand with a pragmatic evaluation of the importance of common sense, self-interest and effort in life. Interviews with truck drivers also confirmed a popular belief in fatalism across the country.

Inscriptions about mothers are also rife. The drivers often quote a prophetic tradition: ‘Paradise lies under the feet of the mother.’ They claim amidst much reverence and visible emotion, that their mothers’ prayers have made them successful. A typical comment, made by Gul Haseeb from Peshawar, is evidence of this mindset:

‘Sahib, if it were not for my mother’s prayers, I would be in jail. Our profession is very tough and it can send a poor driver to the graveyard or the jail while his hair is still black.’

Yet another driver compared his mother to the sun, which gives life to the earth. ‘When the mother dies, the house is cold,’ he said.

It appears that there are more inscriptions about mothers in Sindh, but it must be added that drivers in all provinces of the country showed the same respect and emotion for their mothers in their interviews.

The languages used for inscriptions on trucks are Arabic, Urdu, Pashto, Sindhi, Balochi, Brahvi and English. English is generally used only as part of the registration formula, e.g. Peshawar 12345 and sometimes, but very rarely, for the name of the company on the sides – which is normally English but written in the Urdu script – or phrases like ‘good luck.’ Balochi and Brahvi are used to express all sorts of themes, but they are so rare that I had to make a special effort to find even nine trucks in Balochistan which had inscriptions in these languages. In Sindh, Sindhi is used, but less than Urdu.

The writing in Arabic does not reflect any conscious choice, as it is the language of Islam and all formulaic, liturgical writing in Islamic societies makes use of it; thus it is always present as an icon of Islam. However, the other languages of Pakistan offer choices for the writer of the inscriptions. To the questions about who decides which language to use for inscriptions and on what basis, most drivers and painters replied that they had jointly decided this and the basis was intelligibility. The language, they said, had to be intelligible to them and to the people they came across during their perennial travels up and down the country. Some workshops have diaries or scrapbooks with couplets, which the drivers can choose from. The present author saw several of such books. One owner of a workshop commented on his scrapbook: “These are the most popular couplets in the last 30 years. When I show them to the drivers, they want them all but are limited by the space available.”

Most of the inscriptions are in Urdu, though there were Pashto ones too. The Pashto inscriptions were found even in Rawalpindi, otherwise a Punjabi and Urdu-speaking city. This was explained by painters who referred to the large number of Pashto-speaking truck drivers in all provinces of Pakistan. “We have to cater for the drivers,” said painter Abdul Ghani, while painting a truck near Pirwadhai in Rawalpindi. “If they like Pashto, so be it. Besides, we painters can write in Pashto as well as in Urdu – even in English. Actually, English is the easiest.” However, as Urdu is used in all the urban trade centres of Pakistan, and is the most common language of communication in the country, it is the major language of inscriptions in the country and can be read, understood and enjoyed by most Pakistanis.

Pashto follows Urdu not because it is understood all over the country – indeed, it is not even taught formally in the Pashto-speaking areas for the most part – but because the drivers are mostly Pashtuns and consider it part of their Pashtun identity.They identify with it and carry it with them as a symbol of their Pashtun roots.

However, there are significant differences between the provinces/regions in the use of Urdu inscriptions on the back of trucks. These differences seem to occur mainly in the NWFP, where Pashto is used along with Urdu, whereas other provinces/regions of Pakistan do not use the local languages so often. If the NWFP were to be removed from the data, there would be no significant differences in the use of Urdu on trucks in Pakistan.

Punjabi is not taught formally in most educational institutions though, like Pashto, it is an optional language in some government schools. Yet it does feature on the trucks, as it is regarded as a language of intimacy, jokes and risqué male, in-group bonding. Thus the following inscription: Rul te gayean/par chas bari ayi (I am ruined/But I really enjoyed myself).

It is found on many trucks and hints at sexual adventurism and its consequences. Yet another line, this one hinting at the lover’s frustration with the inability of his beloved to meet him, goes as follows:

Aag lavan teri majburian nun (I feel like burning your constraints). Innuendoes like this are enjoyed by the majority of people, especially men, in Pakistan. Thus, trucks are often a source of diversion on the otherwise frustratingly congested and often pock-marked and cratered roads of Pakistan.

Despite the threat of ‘Talibanisation,’ the inscriptions on the trucks suggest that the world view of truckers (drivers, painters, apprentices and owners of trucks) remains easy-going, romantic, fatalistic, superstitious and appreciative of beauty and pleasure. To call it ‘liberal’ may be misleading, as it does not respect women’s rights or political liberalism. It draws upon a folk Islam, and not the puritanical, misogynist, strict and anti-pleasure variety of Islam which is associated with the Taliban.

Thus, while the extremist interpretation of Islam prohibits amorous literature or the description of female beauty for the gratification of men, South Asian high culture has always valued romantic verse. The inscriptions on trucks operate within the familiar paradigm of South Asian culture in which poetry, especially romantic poetry, is much in demand. The pandering to the ritualistic aspect of religion, as evidenced by the ritualistic inscriptions on the top of trucks, reflects Muslim popular culture in South Asia. Fatalism, a prominent theme of inscriptions, is also a part of the same world view.

This truckers have much reverence for Sufis and their ideas. Proof of this are the inscriptions which refer to popular Sufis and their shrines in Pakistan: Bari Imam (Islamabad), Data Sahib (Lahore), Pir Baba (Buner), Baba Farid (Pakpattan), Shahbaz Qalandar (Sehwan), etc. Other inscriptions on Sufi themes reference unity (wahdat-ul-wujud) and the omnipresence of the deity.

It appears that ordinary people do not object to the romantic inscriptions, but do take offence at paintings of the human figure, which are considered sinful. However, somewhat surprisingly, in response to a question about whether drivers painted women or got someone to do it for them, most drivers replied that they got a painter to paint a woman for them, while some admitted that they first tried themselves and once unsuccessful, turned to the painters. Most painters said it was their favourite hobby. Only one painter who used to paint women has left because he now considers it a sin. Driver Gul Khan, originally from Swat, said: “I tried to paint women. I like Aishwarya Rai a lot, and tried to copy a picture of her. But it turned out funny – [laughing] it was not like her at all. So I gave up and had painters do it for me.” Painter Haseeb Ullah from Rawalpindi told me he liked painting women in tight trousers – often in a police uniform – but since people objected to these, he gave up. “He was forced to give up,” said an apprentice. “His women revealed too much.” Everybody laughed. As for boys – defined as adolescents between the ages of 14 and 18 or so – only a few drivers (15%) said they got painters to paint them, but most denied having done it. Yet, 70% of the painters confessed to painting boys, though one has left doing so on account of it being a sinful activity.

Painter Amanullah from Rawalpindi revealed that many drivers do want boys painted. He tells me that he used pictures of boys in books and magazines for this, and used to like it. Then he adds: “But I heard the story of the Prophet Lut in the Quran, and I never did it again.” Children, however, are liked by everybody. Some said they had greater “emotion” in them than other human figures. It became clear that these children – pre-pubescent boys between the ages of 3-10 – were the sons (daughters are not painted) of the owners or, in some cases, the painter himself. Most drivers complained that they would like to get their children painted on the truck they drive but the owner does not allow them, as they have their own children on them. “I want my sons to be with me but the child here is the owner’s son. Anyway, all children are innocent,” is driver Irfanullah’s comment, a reflection of the general sentiment.

One painter from Peshawar said he did not care for the Taliban and would not listen to them even if they destroyed his shop. A driver reported that he knew of trucks that sported pictures of women being stopped by the Taliban, who warned the driver to remove them.

The Taliban even object to romantic verses, calling poetry itself sinful but they [the Taliban] have generally left them unharmed. Most of them object to human figures, calling them a grave violation of the Shariah. Driver Mahabbat Khan from Mansehra had this to say: “My elders often told me not to paint people or animals. The mullah must have told them about it being a sin. But I still get beautiful poetry written on the truck!” For this reason, some drivers who used to get actresses painted are now replacing them with national leaders. Several drivers from Quetta reported that a police officer who had helped truck drivers many a time, had become so popular that his picture still adorned many trucks from Balochistan. President Ayub Khan was also very popular with the truck drivers, but his picture seems to have gone out of fashion. Most drivers and painters still prefer actresses and actors to anything else. However, Professor Martin Sokefeld, a German scholar who has written on truck art among other cultural phenomena of Pakistan, and has been doing field work in Pakistan since the 1990s, notes that on the sides, portraits of women have become very common. “This can be explained in two ways. Either the drivers’ and painters’ memories go back only to the last two or three years, when Talibanisation began to spread in society, and by this time the trend of making womens’ pictures was already on the rise. Or, perhaps the pictures of women have been moved from the backs of the trucks, where they are more prominent, to the sides.

Going by the inscriptions on the trucks it is heartening to note that the world view of people associated with trucks – mainly drivers but also their assistants, painters and owners – has not shifted to radical or militant Islam yet. It still remains rooted in popular culture, which adheres to low church beliefs and practices. However, this popular culture is undergoing a metamorphosis and may be transformed further as Talibanisation increases but, as of now, it offers the hope that some of the core values of Pakistani culture, which made this country hospitable and lively, may be more resilient than the headlines about suicide bombers, the burning of CD shops and the suppression of the arts might have led us to believe.Huge Brides on the Move - Wonders of Pakistan

Truck art, as any one knows, is one of the great folk arts of Pakistan. These heavy machines affectionately called “brides” by truckers are covered mostly in vivid bright multilayered colors and fairy lights which have a talismanic function of warding off evil spirits and promote good luck – something one needs in plenty when navigating our roads. But apart from this magical effect, truckers have another romance with these brightly colored vehicles.

Salamat a typical truckwala admits that he spends more on decorating his truck than he paid for his second marriage a couple of years ago. “I spend most of my time in my truck. It’s like a second home to me” says Salamat.

WOP contributing editor

and an award winning photographer Umair Ghani went an extra mile at each stop; which he did at the most stopovers (the dining cum resting places on road sides) to have a face to face and heart to heart chat sessions with this trucking community of Pakistan.

“GT Road te duhaiyan pawe, nin yaaran da truck baliyay“

[Look my love, how magnificient does your lover roam on the GT Road]

Standing along a tea stall on the Grand Truck Road near Jehlum, I listen to the upbeat Punjabi Bhangra as trucks in many colors, decos and carvings whirlpass me. In a flash, I conjecture on the assignment I have and just muse on the art of painting especially the art of painting trucks in Pakistan, an art unique to our country. None of our geographical neighbours, neither the Indians in the east nor the Afghanis in neighbouring north indulge in this special art.

My fascination with painted trucks of Pakistan starts from Jamal J Elias of the University of Pennsylvania. I read his article and have an email from him that inspires me to get on road and capture the exquisite beauty of design and color of Bedford trucks moving on the roads of Pakistan.

You see them everywhere,”

Elias wrote in his article, “But a lot of people don’t see them. One day I started staring at them, very carefully. And I started to see there was some order to the madness.”

Elias took six years to compile the monumental work for his forthcoming book “On Wings of Diesel”, and it is still in continuation. I traveled some 5000 km in three months, from Karachi to Khunjrab Pass traversing through deserts, plains, passes and awe inspiring mountains along the KKH. I met many interesting people, roadside artists (Street Picassos I call them) unforgettable experiences in my quest for the unique vehicle art in Pakistan. During all those wonderful episodes of exploration, I had but one consistent inspiration from that genie of Pakistani truck art — Jamal J Elias.

Sipping morning tea from a tiny china clay cup in a roadside truck drivers’ tavern on the banks of river Indus, I looked at the long stretch of Karakoram Highway winding high into the far distance. It was only a night before when I reached Bisham from Lahore. I had been on road for many days without rest pursuing truck caravans bound for Sost [last Pakistani outpost on Pak-China border]. Morning sun shone brightly over the mud roof of driver’s hotel a few kilometers ahead of Bisham. We sat on huge charpoys, sipped more tea as Sada Khan talked about his magnificent red Bedford parked outside. “This truck is my bride. That’s why it is painted red. I have spent most part of my life with it than at my home with parents and the family. Like a newly wed bride, it should look beautiful, enticing and alluring.” relates Sada Khan with the magic touch of an apt story teller of the Asian world. Soon, the tantalizing channa dal and parathas arrive and breakfast begins in a formal manner. Sada Khan relaxes himself on the multi colored blankets piled on the charpoys and continued his tale.

[Right: Me and My Bride]

“I fell in love with truck decorations in Peshawar, where I was a helper boy at truck stations decades ago. I know that an aesthetically decorated truck can make you jealous, envious at best and you cherish the dream to outclass others by more eloquent designs and patterns.”

A normal sized Bedford truck takes three to four hundred thousand rupees to be painted and decorated in style, a sum that amounts to two years’ salary of an average truck driver. Yet, many of them spend whatever fortunes they have on truck paintings. It may take one to two months for the truck to get ready for the road. Truck workshops in Karachi, Ghotki, D.G. Khan, Peshawar, Taxila, Rawalpindi and Lahore are centers of decorative painting (the beauty salons) of these moving “brides”. To some extent truck painting is done in Afghanistan, India, Indonesia, Malaysia and Philippines as well but not so explicitly as they do this here in Pakistan.

[Left: A Blend of Bright, Multilayered Colors]

Here it is an elegant blend of styles, color and designs which is easily distinguishable from their contemporaries elsewhere. The themes of Pakistani truck art are mostly religious, patriotic and cultural. The fascinating diversity of images from secular to religious and sometimes of many individuals, thoughts and views idealise by the artists also come on the moving frames. It includes also famous actresses and cricketers who frequently appear on wooden planks. Winds of cultural change though have replaced leaders, martyrs and other celebrities of the yesteryears with missiles and new age heroes like country’s nuclear scientist Dr A. Q. Khan, after the country stepped into the prestigious Nuclear Club in 1998.

“Patriotic Billboards” as many Westerners label these vehicles, the trucks carry a huge number of religious signs and slogans as well. Images of holy Ka’aba and Madina appear mostly on the upper front (the Taj or crown of a truck) with names of Allah and the Holy Prophet. Verses from Holy Quran are either painted or hung in the form of plastic or metal pieces. Images of birds and animals most notably peacocks, pigeons, lions and tigers are drawn on the side panels. The ever present figure of Ayub Khan behind many trucks in NWFP and Balochistan has something to do with a mix of patriotism and nostalgia of the bygone days in a country which had then poor road infrastructure and almost non existent railroad system for mobilization on a mass scale. In that scenario, came forward Ayub Khan’s son as the country’s sole Bedford dealer (1962 – 1969) and made sure that Bedfords were the only trucks imported into the country.

Locally manufactured truckswere nowhere in the competition and when local artists created breathtaking masterpieces out of Bedfords they swept the market like a storm. J.M. Kenoyer, a renowned scholar of Pakistani culture comments, “The paint jobs identify competing ethnic groups. You look at a truck and can tell exactly what region it comes from and what ethnic group the driver belongs to.”

Through my multiple interactions with truck drivers, I came to know that truck painting for them was a labor of love, “and love makes you suffer”, whispered Badshah in a dingy tea stall in the outskirts of Multan. Truck drivers don’t spend much money on their families and houses. They view trucks as a deity which brings them income, joy and freedom of the road. “It’s kind of Bhagwan for us”, said Badshah displaying his tea and naswar smeared teeth and twirled his thick moustache with the thumb and first finger of the free hand. While listening to Badshah I recalled an article where Durriya Kazi, head of the department of visual studies at the University of Karachi and an encyclopedia on Pakistani truck-decoration, quoted such instances; “I remember one driver who told me that he put his life and livelihood into the truck. If he didn’t honor it with the proper paint job, he would feel he was being ungrateful to his machine.”

The sense of devotion and a bond of love keep the trucker and the truck chained together. For a truck driver, his vehicle is the life’s whole sphere around which circles his life, his love, likes and dislikes. He scarcely looks beyond that. “We don’t have to”, laughed Badshah, “and why should we when we feel protected and enormously proud in our beautiful paradise.” Charas (local brand of hashish), naswar (snuff) and tobacco are amongst some of the pleasures these truckers have in their rugged routines. The glorious art work provides an escape from the monotony of life. Music is another pre-requisite of this nomadic life on wheels. Truckers don’t dance nor even sing but are fond of folk tunes and songs that include regional flare. Atta Ullah Khan Eesakhailvi, Allah Ditta Loonay Wala and Zarsanga are among the most cherished singers. Multicolored laces hang from stereos and speakers covered in beads and plastic decorations which renders the truck’s interior pompously ornamental.

Booming truck painting industry despite all its magnitude and impact may not be a lucrative and lovable vocation for all. The people who work in it, the Sreet Picassos [truck painters] are mostly underpaid. Many ‘Ustads’ and their apprentices commonly called ‘chhotas’ create magnum opus out of a common Bedford for small amounts and scanty privileges. “Big chunks of the money goes to workshop owners”, said Hajji in a typical Lahori workshop famous for plastic and metal work. “This art is a complete exhibition on wheels which involves arduous labor and a careful placement of each piece of colored plastic, every stroke of paint brush and carving and engraving on the panels and sides”, he explains amid chugging of heavy engines and noisy rattle of metal plates. Though well known and respected for their artistic skills, many of them are dissatisfied with marginal wages they earn from their creative art. They wish their kids to join school and get educated for better jobs.

Trucks began to draw attention in the transport industry in Pakistan when construction of major highways started in the country. This boosted transport of construction material business. To attract their customers, truckers started to get their vehicles painted and decorated for more business. More visibly decorated machines fetched better bargains. Stylised murals and bright red color did the job for many truckers. Some shrewd artists painted pictorial allusions that were alien to local culture and visual sensibilities to draw immediate attention. Some drivers [or designers] with a literary flavor, love to paint verses about dejection and betrayal of love. Some verses become slogans of drivers’ ideology and some of their very personal aspirations.

Goods and commercial companies jumped into the art competition and entire fleets of trucks came to workshops to be painted in designs exclusively created for each corporate competitor. A nation of 140 million people needed loads of supplies to be hauled from one part of Pakistan to another, So Bedford, Hino, Volvo, Isuzu and Mercedes ‘ heavy machines traveled in form of chained caravans. Now truck painting is recognized as a form of cultural diversity. Decorated brides of truck drivers move in splendor all across the country with unprecedented pomp and show.

Photographs: Umair Ghani, Mujahid-ur-Rehman, Lahore, Pakistan Plates: Shahidul Islam / DRIC Gallery, Dacca, Bangladesh

Jamal Elias - Looking at Sunni/Shiite Islam in Truck Arts

http://observers.france24.com/en/content/20100108-pakistan-missionary-trucks-shiite-sunni-decoration

All trucks are ornamented with some combination of epigraphic formulae, poetry, repetitive patterns, landscapes, and figural images (beautiful women, political figures, national heroes etc). Traditionally, the decoration with religious significance is talismanic, in that it protects the truck, its content and the driver from misfortune. But in 2003, a religious Sunni group by the name of Tablighi Jama’at started shifting the syntax of truck decoration to advertise their particular message. This activist attitude is pushing other religious groups (Shiite and other Sunni groups) to respond, thus creating the concept of ‘missionary trucks’.”

The central medallion at the top reads “Ma shaallah” (“As god wishes”). Below on the smaller medallion, "Daawat tabligh zindabad" ("Long live the call of Tabligh!) – referring to the Sunni movement, Tablighi Jama’at. Photo posted on Flickr by Amaia Arozena and Gotzon Iraola, Sep. 21, 2009.

The façade of the truck is peppered with Shiite inscriptions. At the top, “Ya Ali madad!” (“Oh Ali help us”), referring to Ali, founder of Shiite Islam. Secondly, in between the pictures of the Kabaa and the Prophet’s mosque, the names of Ali’s two sons, Hassan and Hussein, and the second and third imams. The central plaque refers to the “last imam”, who Shiite Muslims believe will return one day. Photo: Jamal J. Elias.

Interesting Comment - hinting against propoganda

Images

http://web.mac.com/mikespix/iWeb/Site/Pakistani%20Truck%20Art.html

AND

http://www.flickr.com/photos/abro/sets/72157594312151038/

Indian Artist Examining Smilarities between Indian & Pakistani Truck Arti

The Moving Art of Pakistan

Source: http://www.artconcerns.net/2008december/html/myTVmyArt.htmThis time My TV & My Art took me to Pakistan, our neighbour, which is a lot like us but seems exotic to many mainly because of inaccessibility or its ‘difficult to get a visa’ factor. It was for a recce on ‘truck art’ for a special TV show that I have been working on. The trucks there are moving installations. They bring life to dusty grey roads. On the mountains they look like jewel carts, shining differently in the different lights of the sun. That’s what Pakistan’s trucks are to me. They remind me that beauty is sometimes a surprise.

Where there are so many similarities between India and Pakistan, it’s surprising that there’s nothing remotely similar to Pakistan truck art in India. In Pakistan, it takes on an ‘industrial scale’. There’s a whole bazaar dedicated to truck ‘body-building’. It is here that the truck gets its four walls and tankers get huge storage cylinders. Other things like extra bumpers are also added here, the front is given a ‘crown’ and changes made in the chassis at the specific instructions of the truck owner. There’s another bazaar for chamak patti (reflective tape) work and truck accessories. Chamak patti designs turn the trucks into neon ships at night.

At the Painting bazaar, painters fill the rest of the body with intricate patterns. The next stop is the accessories market. The shops here sell parandas, bead strands, stickers, scarves, jhalars etc. The truck now has the glamour of a bride.

Not too long ago, these beauties of the road were seen to be an aesthetic nightmare and plans were initiated to have them grounded. But better sense prevailed when some lovers of art took it upon themselves to revive it in the name of kitsch art. What followed was a gradual international acceptance.

Today, Pakistani truck art is much sought after by collectors and museums from Sydney to San Francisco. Anjum Rana is one the pioneers of the truck art movement. She is also got his year’s UNESCO quality certification. Rana has brought truck art to teapots, mugs, mirror, garden benches, bikes, table fans, jewellery boxes and beach umbrellas. Her efforts of the last decade, has given truck art a place of pride in fashionable homes across the world.

Which brings me to the mention of something else that I feel needs access to fashionable homes across the world. Contemporary Pakistani art. While collectors in Pakistan often seek to invest in masters like Sadequain, Gulgee or Jamil Naksh, Pakistani contemporary art has yet to whet their appetite. But the market for contemporary artists in Pakistan lies abroad. Naiza Khan is listed with Rossi & Rossi in the UK. Rashid Rana and Huma Mulji have caught the eye of Charles Saatchi of Saatchi Art Gallery. Neo-miniaturists from Lahore’s National College of Arts are known and collected for their distinct miniature style. Artists like Waseem Ahmed and Mohammad Zeeshan are immensely popular in India with their politically sensitive miniatures.

The artists’ residency programme, VASL routinely collaborates with its counterparts in South Asia, residencies like KHOJ in India and Theertha in Sri Lanka. Nukta Art, a magazine ensures that a dialogue is kept alive between artists, critics and collectors. And this is just a sneak peek, because the art scene in Pakistan is really raring to go. It’s finally asking for some respect that it’s long been denied. It is letting the world know that they are serious about art and about freedom.

For years, the Frere Hall in Karachi was shut to the public for security reasons as it stands right opposite the US consulate. It was a huge loss because this British town hall that was changed to a public space for art shows, houses a ceiling mural done by Sadequain. It lies half done because he died in the middle of the project in 1987. And this fact lends a sense of being watched over by the artist. But thankfully, there was a public art opening in Frere Hall this November, renovated and crisp, ready to be the art hub that it used to be. The show was titled “Don’t Mess With Karachi”. It was an installation and photography show on the city, waste management and other civic issues that trouble every Karachi-ite!! I strongly feel that a lot more maturity of style and perspective should have gone into the show. Doing a public art show for debuting artists in Pakistan is commendable but the effort shouldn’t end there. It’s also important to make a statement with the works curated for such a show. And perhaps that’s why, I found myself looking more at the decades old Sadequain ceiling instead.

There is also an effort to bring this dialogue out into the public sphere. The Second Floor or T2F as its commonly known in Karachi, is a café that holds an open house every weekend. Artists, writers, poets and musicians come here and share their stuff with the city’s happening crowd over coffee and sandwiches. I showed two of my favourite TV stories. A show on India’s ‘new media’ stars like Subodh Gupta and Mithu Sen and another on MF Husain’s life in Dubai. I was flooded with questions ‘about the art scene there’. When will Husain return? Does Subodh really sell for that much? When will you do a show on Pakistani art?

I also met sculptor Amin Gulgee, he is the son of Gulgee, Pakistan’s Gujral. This December marks a year of Gulgee and his wife’s brutal murder in Karachi. They were beaten to death by their domestic help. Amin is still busy running to the courts, Gulgee’s Clifton bungalow that houses most of his works is currently sealed. There are plans to soon open it as a Gulgee museum. It’s uncanny how on a previous trip to Pakistan I had interviewed Gulgee for an Independence Day special.

The dead usually speak through mediums but the Chaukhandi Tombs, about an hour’s drive from Karachi, don’t need diviners. Built between the 14th and 15th centuries by the Sindhi clan of Jokhio, these tombs are not only breath-takingly embellished but are also a rare record in time. There are no artisans left today who can replicate the Jokhio project in Chaukhandi. The clan survives but its ‘grave architecture’ does not. We met some Jokhios who reasoned that their ancestors probably had a lot of time. But I am still thinking…

Sahar Zaman currently works with CNN IBN as the art correspondent and news anchor